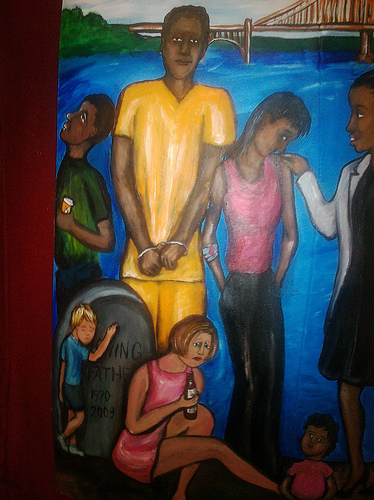

Art in this post by Regina Holliday

A couple of years ago, I was asked to see a young woman with symptoms of urinary urgency, frequency, and pelvic pain. Being a urologist, my first thought was that she probably had interstitial cystitis. Instinctively, as my mind began drifting down the testing and treatment algorithm, I began typing. After a moment or two, I looked up from the keyboard. I noticed her eyes hung toward the floor in a downward, distant gaze.

Stepping Up

For the purpose of this story, I will refer to this young woman as “Mary”, a pseudonym. Concerned, I asked Mary some questions about her life. She had grown up locally in the foster care system, moving from family to family. Currently, she lived with her boyfriend, a relationship that provided Mary with a place to live, but not much more. For a first visit, I felt maybe I had asked enough questions.

As chance would have it, a physician colleague of mine had recently started a nonprofit for children transitioning out of foster care and into adulthood. The program, called Step Up, provides participants with a safe and friendly home. Opportunities for counseling, mentorship, job placement, and spiritual growth are available as well. In addition to discussing her urological symptoms, I talked to Mary about Step Up. She was enthusiastic and wanted to learn more, so I made the referral.

However, when Mary returned to see me a few weeks later, her living situation remained unchanged. Her bladder symptoms were only slightly better. She went on to tell me how she also suffered from recurrent headaches, pelvic pain, pain with sexual activity, and weight gain. As she told me about her symptoms, her demeanor remained calm. But inside her organs were screaming, crying out for help. When I asked her about the referral to Step Up, she confessed that she never followed up. I couldn’t understand why.

Not too long after meeting Mary, I began volunteering for Step Up myself. I came to find that even when a carefully selected group of young women in need are offered shelter, emotional support, and love, some will drop out and return to their previous social and living conditions.

The Effects of Childhood Trauma

On the advice of a professional colleague, I started reading The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk M.D. In his book, Dr. van der Kolk describes the process of how ongoing childhood trauma leads to chronically elevated stress hormones. Over time, this stress level not only changes the body, but also the brain and mind.

Suddenly, a light bulb in my head turned on. For the first time, all of these seemingly unrelated clinical observations and experiences finally started to make some sense.

What stuck with me most were the functional MRI (fMRI) images in Dr. van der Kolk’s book, demonstrating a relationship between traumatic memories and changes in brain activity. When trauma patients are asked to recall a traumatic memory, their scans show clear changes in the metabolism of tissue in specific areas of the brain. Some patients’ brains light up with anger, others nearly turn off as they recall their trauma.

These changes affect a person’s ability to learn new things and can handicap their ability to make choices that could ultimately improve their quality of life. If that were not enough, gene expression, as measured by methylation, has been shown to be altered in trauma patients. This results in DNA changes that have the potential to be passed on from generation to generation.

Now, when I’m I working with some of my toughest patients, I don’t just ask about their symptoms. I ask about what has happened and what is happening in their lives? I invite them to tell me their story.

In the case of Mary, she was barely an adult yet she had already witnessed the effects of alcoholism, drug abuse, and domestic violence and experienced the pain of separation from her home and family. Over time, working with Mary, volunteering for Step Up, and with further reading and study, I’ve started to see my patients, and my community, through a different set of lenses.

Healing with Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

The ancients spoke of happiness as being the result of balance and harmony. Exposure to childhood trauma has been shown to not only disrupt balance, but undermine harmony and happiness in an ongoing, potentially multi-generational, manner.

The good news is there’s a readily available tool you can use in your practice to assess for childhood trauma called the Adverse Childhood Experiences Survey (ACEs). It is only ten questions long. My friend and colleague, Dr. Ramona Wallace, has administered this survey extensively and believes just asking the ACEs questions demonstrates a new level of physician caring, compassion, and empathy.

In my own experience, I’ve found that asking the ACEs questions not only helps the patient, it also helps to heal the healer.

Dr. Wallace views the survey as not simply a list of questions, but also a potentially powerful intervention. We may not all have formal training in psychiatry, but we all have the natural capacity to express compassion and empathy. The organ systems that we treat as specialists don’t exist in a vacuum. Now, when I see patients struggling, I try to make the time to dig deeper.

Recently, I had a bright, second-year, family practice resident on rotation with me. I asked her if she’d ever asked the ACEs questions? She told me she’d never even heard about the survey. A recent study of our community, Muskegon, Michigan, showed a higher than average prevalence of ACEs. Within our physician community, I still think we have a lot of educating to do. I would like to encourage you to consider taking the ACEs test yourself.

A Different Kind of Fixer

As a surgeon, I like to fix things. In fact, professionally, my self esteem is often tied to how well I’m able to fix a particular problem. Treating patients with high ACEs scores has forced me to not only think about, but approach, my patients differently. In an era when entering data into the electronic medical record takes away more and more of our time, these patients need and deserve our undivided attention and time.

In the operating room, I ocassionally listen to a song called “The Fixer” by Pearl Jam. It goes something like this:

‘When something’s broke, I wanna put a bit of fixin’ on it.

When something’s dark, let me shed a little light on it.

When something’s cold, I wanna put a little fire on it.

If something’s old, I wanna put a bit of shine on it.

When something’s gone, I wanna fight to get it back again.

Fight to get it back again.’

– “The Fixer” by Pearl Jam

Most children come into the world with unlimited potential. The consequences of traumatic events in childhood can change that potential. Quality mental health services are often underfunded and frequently difficult to find. As physicians, we have an opportunity to work together to help these young people restore harmony and balance in their lives. In doing so, each of us has the potential to become, a different kind of fixer.

Acknowledgement: I would like to thank Regina Holliday, Founder of the Walking Gallery, for permission to use her artwork for this post. I would like to encourage you to also read Regina’s post about ACEs. You can follow Regina on Twitter @ReginaHolliday.

Hi Dr. Stork! Thank you so much for speaking at Second CRC Grand Haven yesterday (3/10/19). I found the discussion on ACEs fascinating as well as extremely enlightening in helping me to understand the behavior of several people in my life. They, too have suffered from multiple ACEs and need more than the average love and compassion.

Oddly enough, I exited your presentation, got in my car and turned on NPR (on sirius XM radio). Lo and behold a woman was being interviewed as a TED talk speaker on ACEs! She, too was a physician, a pediatrician, and so impressed by the correlation between ACEs and childhood syndromes and diseases.

Great day all around.

Thanks, again!

Thank you, Jane

You have a lovely church and it was great to have such an attentive, engaging audience.

Easter Blessings!

Brian